Black exodus from Berkeley

Amid gentrification and displacement, opportunity heads elsewhere

February 24, 2022

Aishwarya Jayadeep | Senior Staff

In 1970, Berkeley was home to more than 27,000 Black residents. Today, less than half remain.

Black population in Berkeley over time

Black population in Alameda County over time

The charts show the change in Berkeley and Alameda County’s Black population from 1950 to 2020, according to US Census data. As reflected in both graphs, the population steadily increased from 1950-1970. However, in Berkeley specifically, there is a sharp decline after 1970. In Alameda County, we see the population start to level off after 1990, hovering at about 185,000 today. (Note: data do not include residents who reported two or more races.)

According to Brandi Summers, campus assistant professor of geography and global metropolitan studies, the increase in the city of Berkeley and Alameda County’s Black population began during the Great Migration.

While the first stage of the migration entailed the movement of Black people from the Black Belt states to the east coast and midwest, it wasn’t until the second stage that the migrants came to California en masse during World War II.

“Prior to that 1950 period, … you had Black folks being encouraged to come not only to escape Jim Crow racism, but also for opportunity,” Summers said.

That opportunity came in the form of industry, specifically wartime industry, according to Summers. Industries such as shipbuilding and munitions created an abundance of jobs, attracting Black people from states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Those who came to escape Jim Crow, however, were met with more of the same.

As a result of redlining and restrictive covenants, Black migrants were confined to settling in wartime housing in specific areas.

“There was a period in which 90% of the Black population was living in West Oakland,” Summers said. “During that time, you had more dilapidated housing because a lot of it was intended to be temporary war housing, or it was that people were stacked up in multifamily units.”

According to Summers, aside from being thought of as temporary and in a state of disrepair, housing in these areas was “intentionally disinvested.” Instead, Summers said, funds were distributed to white residents so they could move away from the city center and into the suburbs.

Only 20 years later, Berkeley’s Black population leveled off and began to decline around the early 1970s: The community was being displaced.

Enrollment of Black students in Berkeley Unified School District

Enrollment of Black students in Alameda County public schools

According to data from the California Department of Education, Black enrollment in both BUSD and Alameda County school districts dropped significantly after the 1997-1998 academic year.

According to Summers, environmental degradation, gentrification and freeway building have made much of the East Bay inhospitable to Black communities.

“Most of the industrial businesses were in West Oakland, and so, it was easier for people to get to their jobs if they lived close,” Summers said. “But of course, the downside is if you have all this industrial waste or pollution, these aren't the most desirable areas to live in. So typically, it's the most poor or marginalized communities that are left to live in the neighborhoods that are essentially most dangerous in terms of the environmental impact.”

On top of that, the construction of freeways cut the land up in such a way that it separated Black communities from businesses, opportunities and access to the rest of Oakland. According to Summers, the community was sending a message: “We don’t want you here anymore.”

Summers also noted the quality of education while she was growing up in Oakland in the 1980s.

“Oakland Unified School District was notorious just in terms of low standards, low funding and there were a lot of people who felt as though it was pure racism on display,” Summers said. “You’re seeing the ways they’re not training teachers; they’re not providing adequate opportunities for students. And instead, it’s kind of this school-to-prison pipeline.”

According to data from the California Department of Education, Black enrollment in both BUSD and Alameda County public school districts dropped significantly after the 1997-98 school year.

Amid the lessening opportunity of majority-Black neighborhoods in the East Bay, communities in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta arose as opportunities for a better quality of life.

“In the ‘80s and the ‘90s, there were more opportunities for middle-class Black and other people of color to move out to these suburban locations where they're looking for better schools, are looking for more space, bigger homes, etc.,” Summers said. “So you have that happening, which isn't necessarily displacement; it's an opportunity.”

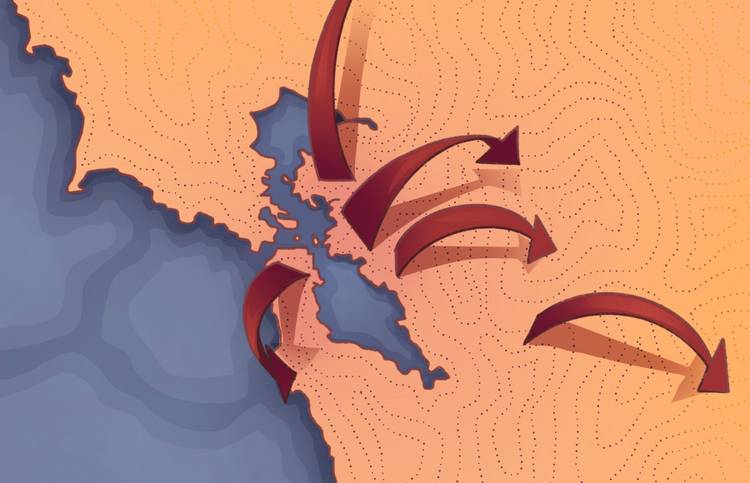

Change in enrollment of Black students between the 1990-91 and 2020-21 academic years

The interactive map provides a school district-specific view of changes in enrollment of Black students across some northern California counties. It visualizes data on the difference in Black student enrollment between the 1990-1991 and 2020-2021 school years in 18 counties in and around the Bay Area, including Alameda, Contra Costa, Lake, Marin, Mendocino, Merced, Napa, Sacramento, San Benito, San Francisco, San Joaquin, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, Solano, Sonoma, Stanislaus and Yolo. The data do not account for students attending private schools or for the many Black people leaving the greater Bay Area or the state of California altogether.

Each circle marker represents a school district. Larger markers represent great decreases while smaller markers signify small increases or decreases in the raw enrollment of Black students in the district. While darker orange markers represent decreases in the percent composition of Black students in each district, lighter orange markers represent increases in the composition. Very small gray dots represent school districts from which data were not available.

In the East Bay, the largest decreases in the percent composition of Black students are in BUSD, Oakland Unified, Emeryville Unified and West Contra Costa Unified. Meanwhile, Antioch Unified, Brentwood Elementary and Liberty Union High in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta see the largest increases in Black student enrollment.

To address the decline in Berkeley’s Black population, City Councilmember Rigel Robinson suggested increasing student housing near campus to mitigate the gentrification of the surrounding areas of Berkeley.

“As the campus grows, students must look further and further from campus to find housing, competing with long-time Berkeley families in the process,” Robinson said in an email.

The student housing search, therefore, prompts landlords and property owners in South Berkeley to cater toward student renters, Robinson added in the email.

Robinson also emphasized the importance of rectifying “the mistakes of the past” through rezoning, especially with the update of the city of Berkeley’s Housing Element, a comprehensive document that will serve as the city’s housing plan from 2023 to 2031, according to the city of Berkeley’s website.

“We must eliminate exclusionary zoning, bring more affordable housing to our neighborhoods, and welcome an influx of new student housing near campus to contain and reverse the student housing crisis and curtail the gentrifying force of the university,” Robinson said in the email.

According to Darrell Owens, transit and housing activist and member of East Bay for Everyone, the trend in Berkeley may even out, but “it’ll never reverse.”

“It’s been a problem for such a long time, … to sound the alarm bells is kind of late at this point,” Owens said. “The vast majority of Black residents have already left. … The solutions we needed were needed decades ago.”

As for the restoration of the Black population in Berkeley and the greater East Bay, Summers acknowledged the need to decouple livability and habitability in order to provide adequate housing for all but recognized that such a process is difficult due to the inherent link between housing and profit accumulation.

Moreover, Summers was uncertain about which factors would draw Black communities back to Berkeley.

“I’m trying to think about the conditions that would make it so that a city would want its most marginalized people to come,” Summers said. “I just can’t see what that would be right now.”

Cameron Fozi is the projects editor. Contact him at cfozi@dailycal.org.

Veronica Roseborough is the deputy projects editor. Contact her at vroseborough@dailycal.org.

Annie Lin is a projects developer. Contact her at annielin@dailycal.org.

About this story

This project was developed by the Data Department at The Daily Californian.

Data for this project come from the California Department of Education and the U.S. Census.

Questions, comments or corrections? Email projects@dailycal.org. Code, data and text are open-source on GitHub.

Support us

We are a nonprofit, student-run newsroom. Please consider donating to support our coverage.

Copyright © 2025 The Daily Californian, The Independent Berkeley Student Publishing Co., Inc.