Reading between the redlines

How 1934 redlining policies meet Berkeley's housing burdens of today

July 18, 2021

What began as an attempt to aid homebuyers and stimulate the economy resulted in the segregation of neighborhoods across the country, with lasting impacts that are still felt by marginalized Americans today.

At the tail end of the Great Depression, more than 1 million Americans faced the foreclosure of their homes and looked to the federal government for assistance. This assistance came in the National Housing Act of 1934’s Federal Housing Administration, which backed homeowner loans and guaranteed mortgages for homebuyers.

On top of existing laws that ingrained racial segregation in daily American life, however, the FHA refused to subsidize mortgages in and around Black neighborhoods. This policy, known as redlining, drew a stark line between Black and white neighborhoods, including those in Berkeley.

Berkeley divisions

In 1937, the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, or HOLC, devised a map of Oakland, Berkeley and surrounding East Bay areas that graded neighborhoods by their respective mortgage security. Neighborhoods were graded as either “A, best”; “B, still desirable”; “C, definitely declining” or “D, hazardous,” with lower grades assigned to predominantly immigrant and Black neighborhoods.

In West Berkeley, which HOLC maps refer to as D3, “favorable” neighborhood influences included its proximity to public transportation, schools and shopping centers. “Detrimental” influences included unpleasant industrial odors, cheap construction and Black and Asian residents.

In contrast, A3 in the eastern corner of the North Berkeley hills was favorably influenced by vistas, improved streets and a “harmonious population with high degrees of culture” while detrimentally influenced by its distance from schools, shopping and public transportation.

These designations resulted in a physical division between Berkeley’s residents still felt today.

“I grew up in Berkeley, and we were always told as kids that the old redline was Martin Luther King Jr. Way, which used to be Grove Street, that Black people were not allowed to build east of Martin Luther King Jr. Way and we all had to live west of it,” said Darrell Owens, transit and housing activist and member of East Bay for Everyone. “If we did go east, you better be like a nanny or something because you’d get the police called on you.”

Though the Fair Housing Act of 1968 made it illegal to discriminate against individuals seeking a mortgage or housing assistance on the basis of race, it ended redlining “in name only,” according to Owens. He claims that the redline still exists in Berkeley but has shifted, preventing Black people from living north of University Avenue and east of Sacramento Street.

On the left, a HOLC redlining map shows the East Bay geographically color-coded by lending security grade.

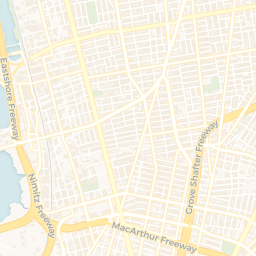

The interactive map displays the housing burden of each ZIP code area in Alameda County. The California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, or OEHHA, defines a housing-burdened household as one with an income of less than 80% of its county's median family income that allocates more than 50% of its income toward housing costs.

Visualizing the effects of redlining

Every few years, the OEHHA releases new data for its pioneering screening tool, CalEnviroScreen, which tracks various burdens that California communities face. We downloaded the CalEnviroScreen dataset and filtered for Alameda County census tracts. We grouped tracts by ZIP code (see the map below for all eight ZIP codes within the city of Berkeley), then plotted results for each noteworthy indicator. Our scatter plots also feature a z-axis attribute, reflected by dot size and color, that represents the housing burden percentile of each data point. Unknown or blank values were omitted.

In the following plots, housing burden refers to the housing burden percentile of one census tract in relation to all other census tracts in California. For example, one census tract that falls in 94705 has a housing burden percentile of 57.15, so its proportion of housing-burdened households is the same as or larger than 57.15% of census tracts in California. All values used in the plots reflect the percentile of a census tract for a given indicator.

Indicator | Description (percentile of...) |

|---|---|

| Groundwater threats | Underground storage tank site leaks near populated streets in specified census tract |

| Impaired waterbodies | Pollutants in all impaired bodies of water near populated streets in specified census tract |

Housing burden

percentile

- < 15

- 15-30

- 30-50

- 50-80

- 80-100

Trends in groundwater threats across ZIP codes illustrate a strong association between housing burden and contamination. For the North Berkeley neighborhoods 94707 and 94708, the approximate median household income is $150,000 as of 2019. Our plot shows that most of the tracts in this area have a housing burden percentile that is less than 15%. Contamination burdens in these areas range from as low as the 0th to 41st percentile and are significantly less than those in 94702, 94703 and 94710 — areas directly west of MLK Jr. Way, the original redline.

Indicator | Description (percentile of...) |

|---|---|

| Pollution | Pollution burden indicators from 0 to 10 as determined by environmental effects and exposures |

| Lead risk | Children’s potential risk for lead exposure in low-income communities with older houses |

| Cleanup sites | Hazardous waste cleanup sites near populated blocks in specified census tract |

| Toxic release | Toxin concentrations in emissions from both on and off-site facilities as determined by risk-screening environmental indicators |

| Hazardous waste | Hazardous waste facilities and large quantity generators near populated blocks in specified census tract |

Housing burden

percentile

- < 15

- 15-30

- 30-50

- 50-80

- 80-100

Lead risk percentiles seem high across the board, with only five ZIP code areas falling below the 50th percentile. Similarly, toxic release is high across all ZIP codes measured, with almost all being between the 60-80th percentile. These measurements may indicate the existence of citywide issues rather than those that affect redlined communities.

Meanwhile, greater pollution and cleanup sites seem correlated with increased housing burden. The ZIP codes with the highest cleanup site percentile are 94702 and 94710, which encompass Northwest and Southwest Berkeley. The western boundary of these two ZIP codes is McLaughlin Eastshore State Park and the eastern boundary is Sacramento Street, the street that Owens deemed “the new redline.”

Hazardous waste sites paint a similar story to cleanup sites. Aside from a few outliers, census tracts that rise above the 75th percentile are concentrated in 94702, 94703 and 94710, all of which are west of MLK Jr. Way, the “old redline.” However, it is important to note these outliers and recognize that even though some communities are higher income and less burdened by housing cost, there are still hazardous waste sites within or near them.

Indicator | Description (percentile of...) |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | Rate of emergency room visits for heart attacks in every 10,000 people adjusted for age |

| Low birth weight | Babies born weighing less than 5 pounds and 8 ounces |

| Asthma | Rate of emergency room visits for asthma |

Housing burden

percentile

- < 15

- 15-30

- 30-50

- 50-80

- 80-100

The cardiovascular disease plot appears to support the well-documented racial and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular health. Areas in the previously redlined communities of 94710 and 94702 see a larger proportion of residents in the emergency room for heart attacks, while the percentiles of the predominantly white population of 94707 and 94708 fall below the 7th percentile.

The low birth weight plot seems more scattered across the board. However, an interdepartmental, public access study from UC Berkeley found that babies born in communities with lower HOLC scores were more likely to be small for gestational age.

Though asthma emergency room visits trend high for all areas of Berkeley except the Berkeley Hills and Thousand Oaks, a joint UC Berkeley-UCSF study found a link between historically redlined communities and asthma-related emergency room visit rates. The study highlighted factors such as increased diesel particulate matter and the psychological stresses of poverty and high crime rates.

Indicator | Description (percentile of...) |

|---|---|

| Poverty | Population living below double the federal poverty line |

| Unemployment | Population that is older than 16, eligible to work and unemployed |

| Education | Population with less than a high school education older than 25 |

| Traffic | Impact of traffic within 150 meters of census tract boundary |

| Linguistic isolation | Households that speak little to no English |

Housing burden

percentile

- < 15

- 15-30

- 30-50

- 50-80

- 80-100

Unsurprisingly, poverty and housing burden appear highly correlated. South and Central Berkeley, represented by 94704 and 94703, hold some of the highest poverty percentiles in Alameda County, with a larger proportion of the population living below double the federal poverty line of $26,500. These areas also hold the highest housing burden percentiles, suggesting a positive linear relationship between income level and housing condition.

The education and linguistic isolation plots reflect similar trends to each other. The area between Berkeley’s borders with Emeryville and Albany west of San Pablo Avenue, 94710, holds the highest proportions of uneducated individuals. The tract with the highest linguistic isolation percentile is located directly west of MLK Jr. Way in 94703, indicating that many households in that area speak little to no English.

Traffic impact is highest in ZIP code areas near a major highway entrance, such as 94710, which is closest to the intersection of Interstates 80 and 580. 94707 and 94708 are much farther from highways and consist mostly of Berkeley Hills neighborhoods and Tilden Regional Park.

“50 years behind”

About 105 years ago, Berkeley became the first city in the United States to implement single-family zoning, a common practice in suburbs that makes building anything other than a single-family home on a single lot illegal.

The policy was implemented in Berkeley’s Elmwood neighborhood in 1916 and from there, expanded to cover half the city, including the Thousand Oaks, Berkeley Hills and Claremont neighborhoods, Owens said.

Owens, who grew up in Central Berkeley, added that his district was zoned for the “unlimited infiltration” of Black and East Asian Americans. In contrast, Berkeley Hills was an “elite district” zoned for single-family homes and prohibited Black and Asian residents.

According to Owens, single-family zoning keeps poorer people out of specific areas, as there is a lack of more affordable multifamily housing such as apartments. Coupled with the refusal of white residents to sell their homes to Black residents, he added, this further exacerbated neighborhood segregation in Berkeley.

That is why, Owens noted, Berkeley’s move last February to replace single-family zoning in the next two years was “the most meaningful thing Berkeley has done in maybe 50 years.”

“It has to take a two-year process just to agree on what to replace it with if they even replace it at all,” Owens said. “Because when you do something, if it's performative, it'll get done really quickly. If it's meaningful, it'll take a generation worth of battling.”

Beyond outlawing single-family zoning, Owens thinks Berkeley should provide more opportunities for higher-density zoning in the city.

“Berkeley is going to have to build an ungodly amount of housing to stop our housing crisis,” he said. “We’re 50 years behind.”

Even with housing crises abound, Owens is sure that Berkeley will see pushback in such efforts. He cited his neighbors’ attempt to build an accessory dwelling unit on their property and recounted that their surrounding neighbors fought against the addition for two years.

“The new strategy in Berkeley is letting the zoning changes go through but making it as hard as possible to actually build anything in other ways,” Owens said.

Though the redlining of the early 20th century is long abolished, data reveal present-day inequities, such as linguistic isolation and poverty, in Berkeley that mimic the borders drawn by the HOLC in 1938. Such disparities are clear within what Owens calls “the new redline,” which has survived in Berkeley through the city’s invention and long defense of single-family zoning policies.

The remedy to the city’s racism and housing crises lies not only in the Berkeley City Council’s recent decision to remove single-family zoning. It will rely on a newfound support for higher-density zoning amid retaliation from community members lest we risk furthering the injustices and bleaching of the city of Berkeley.

Shannon Bonet is the deputy projects editor. Contact her at sbonet@dailycal.org.

Cameron Fozi is a projects developer. Contact him at cfozi@dailycal.org.

Veronica Roseborough is a projects developer. Contact her at vroseborough@dailycal.org.

About this story

This project was developed by the Projects Department at The Daily Californian.

Data for this project come from the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment's CalEnviroScreen 4.0 dataset.

Questions, comments or corrections? Email projects@dailycal.org.

Code, data and text are open-source on GitHub.

Support us

We are a nonprofit, student-run newsroom. Please consider donating to support our coverage.

Copyright © 2022 The Daily Californian, The Independent Berkeley Student Publishing Co., Inc.